Brown Argus

Brown Hairstreak

Chalkhill Blue

Clouded Yellow

Comma

Common Blue

Dark Green Fritillary

Dingy Skipper

Essex Skipper

Gatekeeper

Green Hairstreak

Green-veined White

Grizzled Skipper

Holly Blue

Large Skipper

Large White

Marbled White

Meadow Brown

Orange-tip

Painted Lady

Peacock

Purple Emperor

Purple Hairstreak

Red Admiral

Ringlet

Silver-washed Fritillary

Small Blue

Small Copper

Small Heath

Small Skipper

Small Tortoiseshell

Small White

Speckled Wood

Wall

White Admiral

White-letter Hairstreak

Extinct/rare immigrants

Small Tortoiseshell

Aglais urticae

General Distribution and Status

The Small Tortoiseshell was a common and widespread resident throughout Britain but there has been an alarming reduction in numbers since the mid 1990s with 2023 and 2024 being the two worst years since 1976. It is widely thought that a parasitic fly Sturmia bella is largely responsible for the decline. The parasite is an immigrant from Europe and has increased in numbers owing to global warming which seems to correlate with the drop in the butterfly's abundance. However, between 2005 and 2014, numbers picked up, spectacularly so in 2013 and 2014 (Fox et al.) which may suggest that the species was building up a resistance to the parasitic fly. Another possible reason for the fall in numbers is the application of neonicotinoid pesticides on field margins where wild flowers and larval foodplants can absorb chemicals adversely impacting insects including butterflies (Gilburn et al.). The situation In Hertfordshire and Middlesex reflects what is occurring nationwide in terms of abundance (Wood, 2016).

| United Kingdom | Herts & Middx | |||

| Distribution | 1976-2019 | +0.2% | 1980-2015 | -6% |

| Average 10-year trend | +0.05% | 2006-2015 | +35% | |

| 2024 since 2015-19 | -26% | |||

| Abundance | 1976-2024 | -86% | 1980-2015 | -29% |

| 2015-2024 | -76% | 2006-2015 | +420% | |

| 2023-2024 | -64% | 2024 since 2015-19 | -89% | |

UK distribution map

UKBMS Species summary

Habitat Requirements

This species can be seen almost anywhere from gardens to mountains but it is most abundant where nettles abound.

Larval Foodplants

Common Nettle Urtica dioica, Small Nettle Urtica urens.

Adult Food Sources

Heather Erica sp. (10001), Buddleia Buddleja davidii (1390), Creeping Thistle Cirsium arvense (1184), Hemp Agrimony Eupatorium cannabinum (1052).

Historical Records

Early reports suggest that the butterfly was common and generally distributed throughout the county. It was plentiful in the autumn of 1953 (Bell 1955) and the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bell 1970, 1971, 1972, 1977).

Local Distribution and Abundance

As shown on the map, the butterfly occurs all over the Stevenage area. 2004 was an extraordinary year around Burleigh Farm and Graffidge Wood where Ken King counted over 250 in July but generally 2014 was found to be the best year during the survey. The largest populations were found in Great Ashby Park, where 53 specimens were recorded on 16 June. The vast majority of visits until 2014 yielded single-figure counts when 30 years ago, finding dozens would be a common occurrence in season. Numbers have dropped significantly each year since 2014. 2024 appeared to have been the worst on record with only 27 reports of 47 individuals and 12 of those occurred on one visit at Canterbury Way Park on 14 July. No reports received in the autumn as is mostly evident in the recent past which suggest the butterfly is now entering hibernation early and skipping a generation.

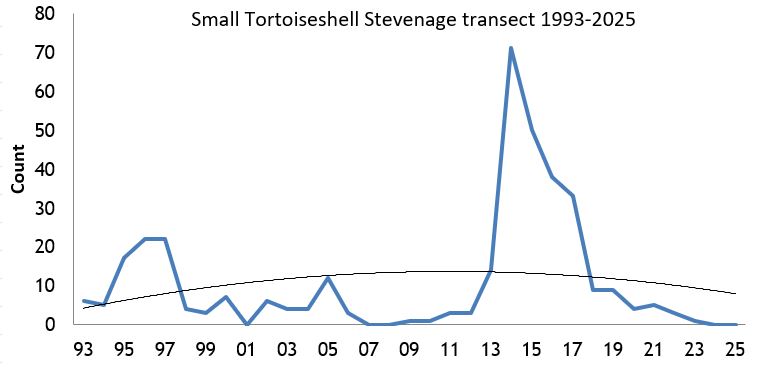

Stevenage (South Fairlands Valley Park) transect 1993-2025

The numbers of this species reached a peak in 2014 as indicated on the chart but have fallen each year since then. A possible reason for the increased abundance in 2014 is increased resistance by the butterfly to a parasitic fly as mentioned above but populations can be boosted by influxes from abroad. The dramatic drop in 2018 might be due to the cold weather in early spring which reduced opportunities for mating and females laying her eggs. No recovery was apparent thereafter.

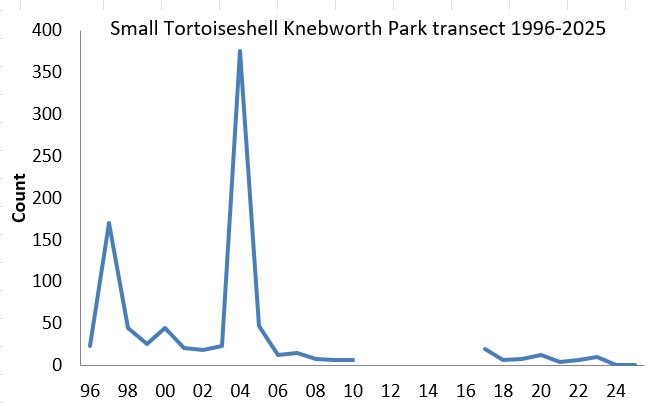

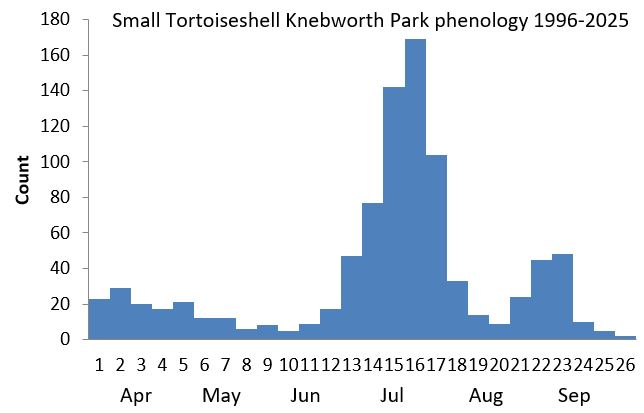

Knebworth Park transect 1996-2010 and 2017-2025

There was an explosion of Small Tortoiseshells in July 2004 as noted above but numbers fell since then and only single figure annual counts recorded by the end of the decade. However 2017 brought numbers up to 20 but very few were seen in the second generation but since then saw numbers drop to single figures apart from 12 reported in 2020.

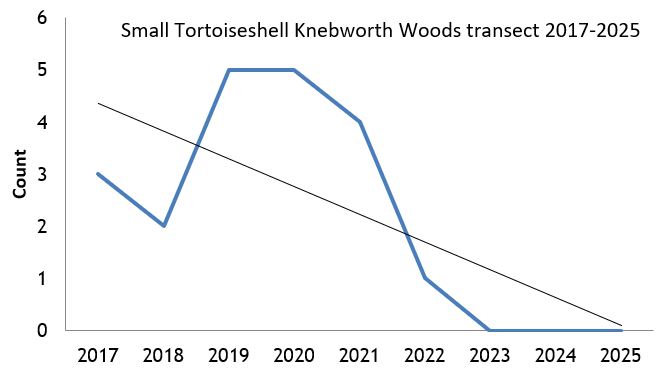

Knebworth Woods transect 2017-2025

Only 20 specimens were reported, scattered throughout the transect. Only one was seen and last recorded in 2022.

Pryor's Wood transect 2000-2022

Eight records of the butterfly were submitted: 2003 (2), 2008 (1), 2013 (1), 2014 (1), 2015 (1), 2018 (1) and 2019 (1).Life History

Earliest date: 1 January 2022 at Fairview Road/Julians Road, Stevenage

Latest date: 1 November 1997 at Monks Wood

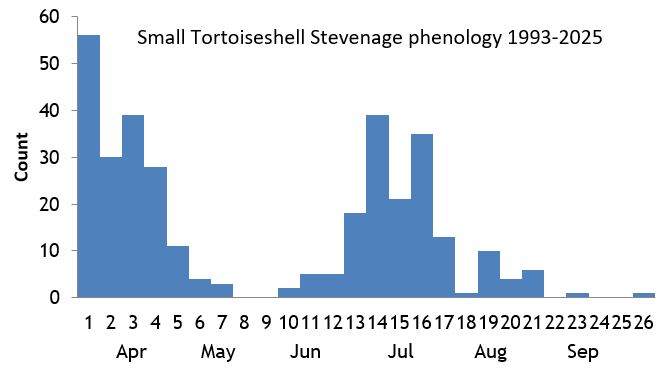

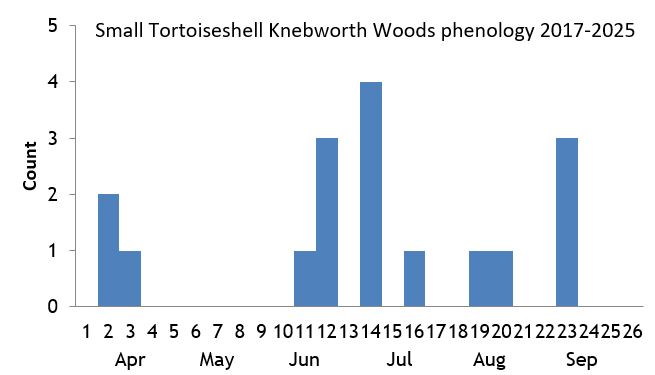

The Small Tortoiseshell usually

produces two broods a year. Overwintering adults often appear on the first warm days of the year, even early as January and continue flying until early May.

The first new generation emerges in around June and some of these adults eventually go into hibernation and others will produce another brood in late

August. It is possible that specimens seen in October and beyond are from a partial third generation. Malcolm Hull's observations of this butterfly

hibernating in his St Albans garden shed suggest that many adults now enter hibernation earlier in the summer perhaps indicating a 'lost generation'

(second brood). The recent drier summers would probably have impacted on fresh growth of young nettles hence reducing potential fecundity of females and

not producing healthy second brood adults. If fresh nettles are thin on the ground do adults 'give up' and not attempt to mate until the following spring?

Populations are subject to immigration and emigration so numbers can vary enormously. Females lay eggs on nettles in mostly open and sheltered situations, and prefer young fresh shoots of the plant. Larvae

construct a chain of webs at the top of the nettles from which they feed. When fully grown they disperse to pupate attached to a leaf or stem.

Behaviour/Observation notes

It usually spends mornings feeding and basking so this is probably the best time of day to get close-up views and take photographs. Males set up territories in the afternoon on nettle beds and mating occurs often very late in the day, which is partly the reason why few photographs of mating pairs are captured.

Variations/Aberrations

There are in excess of 105 named aberrations known to occur in Britain. Much work has been done on how extreme temperatures can affect

development in the early stages and the pigments in the adults. Many aberrations are a result of these environmental factors but many others are nevertheless

genetic (Eeles). One of the more common aberrations is ab. nigrita where the hindwings are almost entirely dark brown.

Find out more on the UK Butterflies website

References

Shackledell Grassland 10 Jun 2014

Fairlands Valley Park 15 Mar 2017

Larvae Fairlands Valley Park 21 Jul 2014

Larva Norton Green 2 Jun 2017